Video documentation by Greg Harm, Tangible Media

This recital is the second in a series comprising a Doctoral project studying the function of the baroque violin in the context of the 21st Century. The research aims to develop, define and document a comprehensive catalogue of extended approaches for the baroque violin that may be used to create new repertoire for it in the 21st Century.

This recital consists of canonic works of the late 20th Century for the modern violin. Each of the pieces in this programme uses either the instrument, or the performer, in extended ways, including some of the most extreme and inventive approaches to creating new sounds developed for the modern violin.

It is notable that many of the extended approaches used in this repertoire, such as glissandi, sul ponticello, sul tasto, microtonality and scordatura have historical precedents on the baroque violin, which were explored in the first recital of this research project. Nevertheless, these approaches, which may not necessarily be new, may be considered extended in the sense that they remain outside the repertoire of the majority of violinists today.

A study of contemporary repertoire for modern violin has proven essential to the research project. Understanding the technical and timbral capacity of the modern violin, through the inventive use of it in recent canonic works, informs the potential means by which the technical and timbral capacity of the baroque violin can be explored and exploited further into the future.

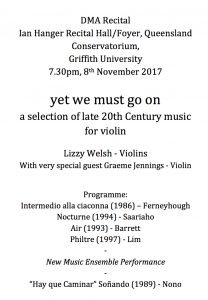

Programme:

Intermedio alla ciaconna (1986) – Ferneyhough

Nocturne (1994) – Saariaho

Air (1993) – Barrett

Philtre (1997) – Lim

–

“Hay que Caminar” Soñando (1989) – Nono

Performers:

Lizzy Welsh – Violins

With very special guest Graeme Jennings – Violin

Intermedio alla ciaconna (1986), Brian Ferneyhough (b. 1943)

One of the foremost proponents of New Complexity, USA-based, British composer Brian Ferneyhough wrote his first solo violin work, Intermedio alla ciaconna, for Irvine Arditti in 1986.

A true chaconne, the work is based around a sequence of eight chords. As the work progresses, becoming ever more complex and ornamented, the harmonic progression is increasingly veiled. Harmonics, extremely high register and microtonality are utilised often; however, the piece typically employs the violin in the timbre most commonly associated with the instrument. The extended nature of the piece comes from its extreme complexity of rhythm and pitch material, thereby extending the violinist rather than the instrument itself.

An interesting notation in the score, also harkening back to early Western art string playing, is the use of tablature. Whilst not used specifically for the violin in the 17th Century, tablature was understood by string players of that time, as it was in common usage on the violas da gamba and viola d’amore. Tablature is used seldom in this work, but has been explored in greater detail by subsequent New Complexity composers.

Nocturne (1994) – Kaija Saariaho (b. 1952)

Dedicated to the memory of Witold Lutosławski, Kaija Saariaho’s Nocturne was first performed by fellow Finn, John Storgårds, in 1994.

The use of fluttering harmonic trills and arpeggios evoke the famous Nocturnes of 19th Century pianist Chopin. Wide timbral ranges of the violin are explored through varied bow position and pressure, simultaneous arco and pizzicato, and double stopped lines mixed with harmonics. Melodies fading in and out of polyphony, or arpeggiated, become more frenetic before dissolving, releasing a space for reflection in sadness at the loss of a friend and mentor.

The ideas explored in Nocturne were incorporated into Saariaho’s violin concerto, Graal Théâtre, of the following year.

Air (1993) – Richard Barrett (b. 1959)

British composer Richard Barrett wrote Air for Mary Oliver in 1993. Part of the larger ensemble work Opening of the Mouth (1992-7), the work breathes through extremely long phrases, interrupted by occasional gasps, splutters and panting.

Another exponent of New Complexist composition, Barrett stretches not just the brain of the violinist, but also the limits of physical possibility, through extreme bow positions, complex chords, harmonics and microtonality. Both hands of the violinist are continually morphing and distorting to almost impossible shapes within a single breath.

The title “Air” brings to mind not just respiration but also the compositional form emerging in Western art music at the beginning of the baroque era. The constant breathing and vocal qualities of Air strengthen the connection to the traditional, song-like form.

Philtre (1997), Liza Lim (b. 1966)

Australian composer Liza Lim wrote Philtre in 1997 for Mary Oliver and Jagdish Mistry. The piece is scored for the Norwegian folk fiddle known as the Hardanger fiddle, or for solo re-tuned violin.

Scordatura, or retuning the violin strings to atypical pitches, is not a new idea by any means. 17th Century violinists explored scordatura extensively in works such as Biber’s famous Rosenkranz-Sonaten of 1676. However, Lim approaches the violin in many new ways in Philtre, through extreme, distortion-creating sul ponticello, complex rhythms and ornamentation incorporating harmonic flutters and glissandi. The use of unison string crossing, made possible by the retuning of the strings, creates such great resonance that one can imagine the sympathetic strings of the Hardanger fiddle even when the piece is performed on the modern violin.

A piece that can already be played on two different instruments, the performer is working with Lim on a performance of Philtre on the baroque violin, which will follow in the third recital of this Doctoral research.

“Hay que Caminar” soñando (1989) – Luigi Nono (1924-1990)

Italian composer Luigi Nono’s final completed work, “Hay que Caminar” soñando, was written in 1989 for Tatiana Grindenko and Gidon Kremer. In it, the violinists must find the music, and one another, whilst traversing the performance space.

Based on the scala enigmatica (enigmatic scale) used by Giuseppi Verdi in his Ave Maria (sulla scala enigmatica) of 1889, Nono’s duo extends the timbre of the violins through col legno, high artificial harmonics, and extreme bow positions and registers. The performance space is likewise extended by the violinists moving through it rather than performing to the audience from a stage, reminiscent of 17th Century examples of spatialised performance to create echo effects, such as Biagio Marini’s Sonata in Ecco of 1629.

“Hay que caminar” soñando (“But we must go on” dreaming), is the final in a set of four works inspired by an inscription Nono saw etched on the wall of a monastery in Toledo, Spain. “Caminantes, no hay caminos, hay que caminar.” (Travellers, there are no roads, yet we must go on.) This sentiment is a reminder of the purpose of my research project, which endeavours to find a path for the baroque violin into the future.

Special thanks to: Kieren Naish, Graeme Jennings, Vanessa Tomlinson, Stephen Emmerson, Liza Lim, Richard Barrett, Jodie Rottle, Steve Newcomb, Rebecca Lloyd-Jones